In late 2019, I was in a rut professionally. I wanted to hone my business skills but kept hitting walls.

It wasn’t for lack of work. Every role provided opportunities but my team’s primary responsibilities were technical so my team didn’t understand why I cared about non-technical work. If I pushed, they’d simply say “that’s the way it is.”

I felt stuck. And it sucked.

On a whim, I joined two ex-colleagues in an exciting venture they assured me would allow me to practice both my technical and business skill sets.

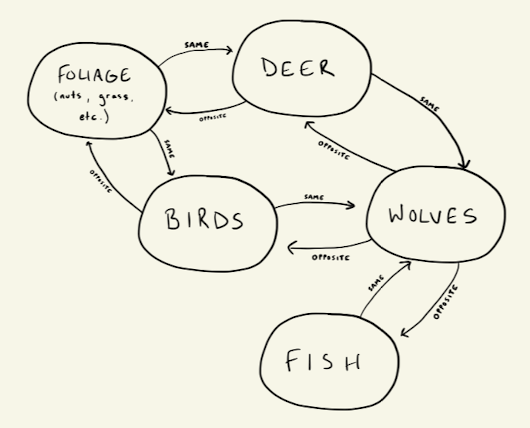

Systems in Nature

My boss and I spent some time getting to know each other in our first one-on-one. I talked about my background in DevOps and she talked about her background in nature ecosystems.

That’s right: nature ecosystems. She started her career studying how plant and animal populations in a given geographic region impact each other–like how a predator population thriving might cause a prey population to dwindle.

She noticed this relationship existed among all plants and animals in the region. Each group’s behavior influenced other groups’ behavior, and vice versa. They depended on each other for survival.

This is known as a system: a group of interdependent parts (the plants and animals) that form a complex, unified whole with a specific purpose (in this case, survival).

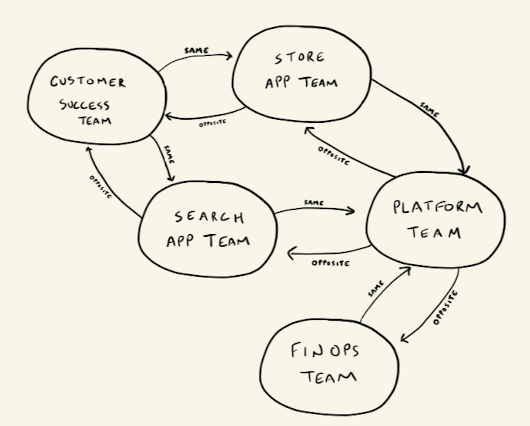

And she realized these systems exist in technology companies too–the only difference is the names of the interconnected parts.

As she talked, I had the following flashback.

Systems in Organizations

Years ago, I worked in an engineering team that managed a subset of my company’s core product. We attempted to optimize all aspects of our microservice but could never quite get the results we wanted.

Eventually we realized our microservice itself wasn’t the bottleneck. The places where our microservice interacted with other parts of the product were the bottleneck.

Weird intermittent errors? Happened when other teams deployed new builds that weren’t compatible with our existing build.

Query response times not going down? The function included a call to a microservice outside our control.

And ironically, our microservice was causing the same problems for other teams.

There’s a joke about two fish swimming together. One fish says to the other “how’s the water today?” and the other replies “what the hell is water?” The joke is that we’re not always aware of our surroundings. We get so caught up in our routine, in our microcosm of focus, that we don’t know about “the big picture”, the holistic system we’re working within.

This is exactly what happened to my team: we didn’t know about the water we were swimming in. We didn’t know how our actions impacted others, and thus couldn’t change how our actions impacted others.

Not Knowing is a Risk

This was my path forward. When my boss gave me visibility into systems, I realized my previous lack of visibility had caused my rut. I had inadvertently proposed work that required systemic visibility without understanding what systemic visibility was or why it was important. Subsequently, my team didn’t buy into any of it.

And I don’t blame them. Throughout my career, nobody told me or my teams about the water we were swimming in, the system that connected us to other teams and required TLC to ensure our company’s success. Existing sprint and roadmap planning processes were accepted as-is because “that’s the way things are” rather than because that’s the way we deliver maximum value to users.

Lack of discussion about the systems that make up our organizations is a business risk.

When a team doesn’t know how its work impacts other parts of the business, it’s far more likely to take actions that slow or prevent the company from achieving its goals. A platform team I worked in believed documenting our deployment processes was a waste of time. What they didn’t realize was the target audience for our platform struggled to use it due to poor documentation. Without this documentation, deployment velocity decreased, and key feature releases and bug fixes were delayed.

And this risk isn’t limited to technical teams. In a previous role, my Head of Marketing regularly asked my team to write technical content. The requests were rarely fulfilled because my team’s primary focus was client projects. My team didn’t realize less technical content decreased the success of marketing campaigns, and attracted fewer potential clients.

Ask Your Doctor if Systems Thinking is Right for You

Now when I join an engineering team, I immediately ask how my team fits into the organization. One of my favorite activities is comparing roadmaps to identify incongruences, competing priorities, and misaligned incentive structures.

This may seem like a business skill that only project managers or product owners should care about but understanding how one’s actions impact other parts of the organization is equally important for engineers. It should be part of onboarding for every employee. Long gone is the information silo era (hopefully). We need to educate employees on systems thinking for the business context era.

If you aren’t sure how your team’s work impacts other teams in the organization, ask. Normalize systems thinking–it’s not just about OKRs and business strategy. Be the change you want to see.

And if you know how your team’s work impacts other teams in the organization, you should still ask. Your mental model may not line up with others’.

The more visibility we have into how we work together, the better we can work together. Simon Sinek once said “people don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it.” Systems thinking helps me understand the “why” behind each team I work with so I know how to help them and our company succeed.

Cover image by Brett Sayles.